A few weeks ago, I was invited to speak at an event on women’s participation in Gambian politics. The discussion became an informal one where we sat in a circle and exchanged stories of our experiences in our private and public spaces, connected by a common desire for freedom as women.

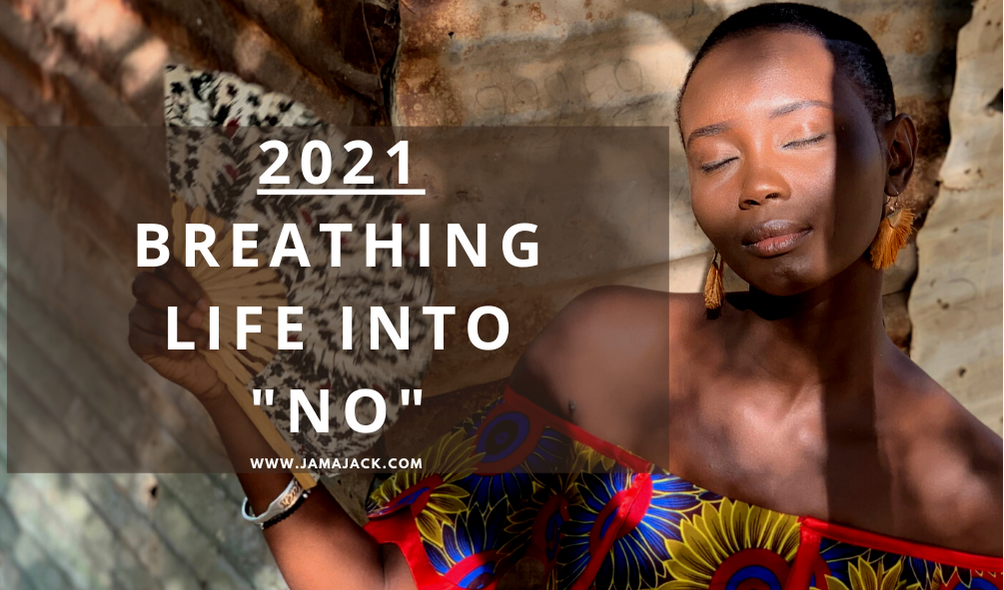

In response to a question I got from one of the girls, I shared that I had found a lot of power in saying “no” and not feeling any guilt about that choice.

As this year ends and I reflect on what my journey has been, I realise this may have been my highlight, even amid so many great accomplishments. It has taken years of strengthening my voice to say “no” without shaking or breaking and teaching myself to soar above the guilt of “would they think I am bad for not saying yes”.

A lot of this has come from a journey of understanding and being intentional about embracing self-care, even as I remain rooted in service to community, humanity and all that is bigger than my individual satisfaction. My feminist relationships and engagements have been constant reminders of the importance of pouring from a cup that is not empty and speaking from a throat that is not parched from the continued sacrifice of self, even if unintentional.

It is a tricky road to navigate; this road about caring for self without being selfish… the one about being for the collective without ignoring self. It’s a road that is filled with so many questions, and few answers that can help to create an easy balance. It is one that eventually forces an introspection that allows for the person travelling to choose what really works best for them. Because, in reality, there is no one answer that clears all the questions for everyone.

Towards the end of last year, I was forced by my experience of living through and working on the COVID-19 pandemic to set intentions for my care and wellbeing, and ensure I wouldn’t end this year 2021 tired, depleted and burnt out from the exhaustion of working nonstop, but especially from saying yes to everything just so I can continue to show up and support.

This meant establishing new boundaries and fortifying existing ones, along with the intentional labour of dealing with the reactions – overt and subtle – to these choices and ensuring their applicability across all aspects of my life. While I like to think of my life in its many elements and facets, and understand myself through the different identities I claim and the variety of things that I do, I am always reminded that they are all connected to one source: me. And that source needed to stay alive and nourished for everything about it to thrive.

I ended last year with a gift to myself: a beautiful cake from my preferred vendor. When I ordered the cake, I gave a simple instruction: I want a cake to celebrate myself for surviving this year. The lady made me one and added one word that I’ve carried with me through this year: Breathe. What was a gift to myself turned into a gift from her, because this year has been one of truly breathing and allowing myself rest when I need it.

It’s the many breaths I have taken to get myself grounded in the reminder of my set intention before responding to a request to do something I didn’t have the capacity for at the time, or that I simply did not want or care for. The invitations to speak at events, several media interviews including one that was going to be a feature in a big international media network, nominations for things, invitations to apply for other things, offers for work with promises of “a lot of money”.

In breathing, I taught myself to stop apologising for turning down requests, opting instead to be direct about the reasons I may not be able to honour them at the time, where I felt this explanation to be necessary. Where I am able to recommend an alternative or a replacement, I do that.

And then I breathe…

Looking back, I realise this simple but tough act became easier with each new time that I did it. I am now ending the year with no regrets and a deep appreciation for the intentions that I set at the end of the last year, satisfied that I have been able to show myself – and those close enough to me to know about my journey – that it is okay to say no to things that you don’t have the space for. Beyond things, people too. But I’ll leave that part for another day.

Away from this satisfaction, there is the truth that in saying no to everything I did, I created more space for the things and people that I really wanted. I was able to give of myself, my time and my resources in the best ways I can to all the things and people I wanted to say “yes” to, and it has been an incredible year.

With my sisters, I launched the Musso Podcast, born from an idea that has lived in my head and heart since 2014, and its birth has been a glorious affirmation.

With my husband and our partners, we have produced two films on a subject that is very important to me. With these projects, I have seen my creative journey grow even further as I stepped up to write and produce both films, in addition to project management and brand communication responsibilities. The results have been excellent, and I can’t wait to share the final products with the world. In my work, I have continued to push beyond boundaries while remaining steadfast to my values and principles.

These are just a few examples from a long list of things that I have achieved and am proud of this year.

I continue to exist and contribute to building feminist community around me, supporting what I can and praying success for what I can’t. A difficult truth I have come to accept is that I do not have to be in community with everyone simply because we share similar interests. When that difficulty lifts, there is much liberation in settling where you feel the light, grace and love to serve and lend yourself to be served. I am grateful for all the communities I have been a part of and continue building.

I have held on to and intentionally worked on relationships that matter to me in family, friendship, and work. Some of it is still work-in-progress as (almost) broken things often take time to mend, but I’ve found bliss in learning to cede to my vulnerability and allowing my feelings to run their course. I’ve also found freedom in releasing what is not meant to stay, and there is a lightness there which, like light, illuminates what remains.

This year has been one of answered prayers, like God was reminding me who is in control and leading my spirit into submission to that which was written for me. I remain faithful. I remain grateful.

This year, I breathed.

Next year, I wish to soar. Higher than I have ever done, and to horizons that ensure my breath remains free, my burden is light, and my liberation is true.

I wish to go even deeper into my journey of creative activism, using my talents to amplify the voices around me and tell stories that matter. The past few years have shown me new directions in that journey, providing soft grounding for my feet, my heart, and my soul.

Next year, I will soar.